Reverse Engineering through Performance Analysis

Overall purpose:

Some computer scientists I admired greatly took a computer systems class, and didn’t like it because it was all about learning about lots of gritty details which didn’t seem to matter very much. I found this greatly disturbing: I have always deeply, appreciated computer systems, especially the attempts to make systems work faster under the hood.

So I decided to write down my own ideas about systems, and see if it helps someone understand them better.

- Successful computer systems are based on engineering and mathematical principles while taking into account historical and physical problems. If you really understand all the principles and problems involved, then much of systems is reasonably strait forward to derive from scratch.

- Performance enhancing systems are easiest to understand by trying lots of things, and measuring performance.

- Actual science is only useful to develop new systems. Understanding existing systems is best done without the rigor and detail of scientific techniques (admittedly, sometimes you need that rigor to be credible to other experts, but certainly not at a student level, and usually not at the working professional level).

So I will go through two strongly related performance enhancing systems, CPU architecture and compiler optimizations, and show how you can use analysis of the problems, key principles, and performance timings to understand why everything works the way it does.

Introduction to key ideas

Parallelism

Why do we care about parallelism?

Basic circuits are inherently sequential: one transistors needs to switch before the next one can, and that switch is a physical change that takes time.

You can make the transistors change faster by increasing voltages. Unfortunately, using this technique there is a rather unfortunate physical property where \(\text{Power} = \text{Clock speed}^2\), so quite quickly, your silicon chip will simply melt if you increase the voltage to increase clock speed.

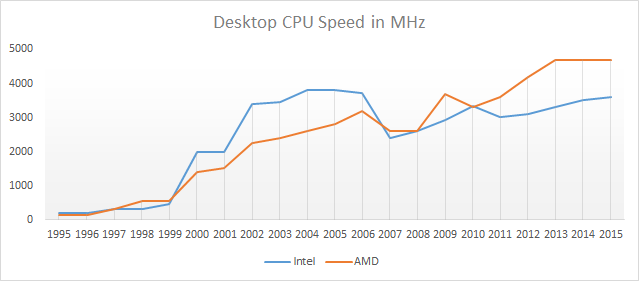

What this means in practice is that there is a limit to how much you can increase speed by increasing voltage. In fact, that point was reached a long time ago.

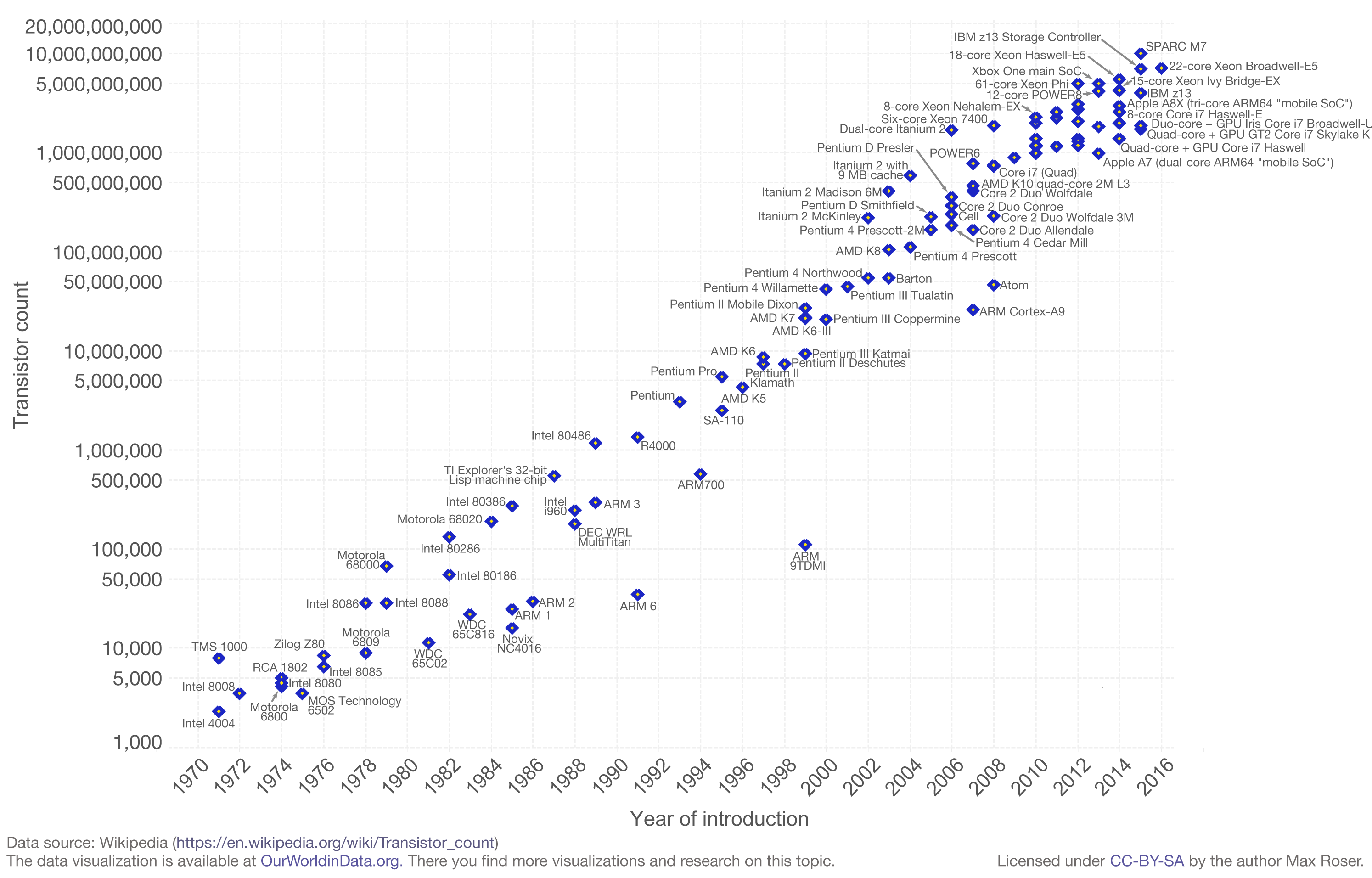

Meanwhile, More’s law continues:

So how can we use those extra transistors?

Here is an idea: instead of trying to use 1 circuit faster, lets try to use a bunch of circuits at the same time. In other words, lets try running our computations in parallel.

What is parallelism?

Before running a computation, you often need other computations to be run first.

From a hardware perspective, you can view this as circuit depth. From a software perspective, you can see this as data dependency chain.

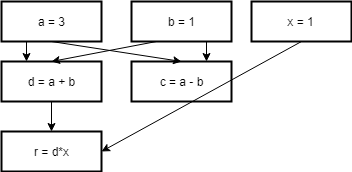

Here is some silly example code

a = 3

b = 1

d = a + b

c = a - b

x = 1

r = d * x

Here is a dependency graph of the code

You can also do this for arbitrarily long code. The idea of “reductions” (as in the MapReduce paradigm) is based on this.

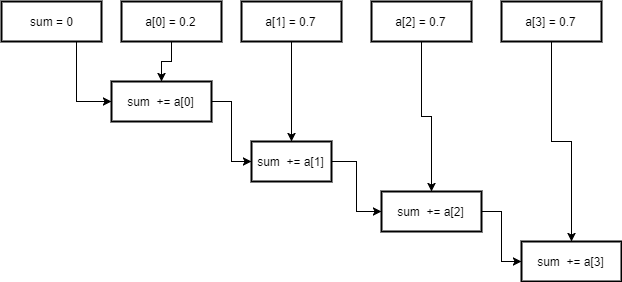

sum = 0

sum += a[0]

sum += a[1]

sum += a[2]

sum += a[3]

This has a circuit depth of 4. How can you lower that depth?

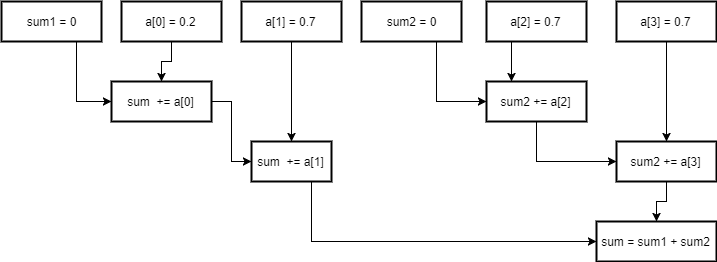

Well, addition is associative, so what if we start adding the middle?

sum1 = 0

sum1 += a[0]

sum1 += a[1]

sum1 += a[2]

sum2 = 0

sum2 += a[3]

sum2 += a[4]

sum = sum1 + sum2

This has a depth of 3, so we made it faster. You can generalize this process to n associative operations, resulting in depth of log(n).

Hopefully you can believe that this is a general and powerful method of identifying parallelism. In fact, we are very close to an nice theory of optimal parallelism.

The famous complexity textbook Introduction to the Theory of Computation by Michael Sipser uses the following definition of parallel complexity.

Parrelell time complexity of a boolean circuit is its depth, or the longest distance from an input variable to the output gates

All sorts of nice things arise out of this definition. You can define optimal speedup with a parallel processor to be:

\[\frac{\text{size}}{\text{depth}}\]Which allows easy analysis with napkin based calculations.

You can also get some nice theoretical results out of this (Sipser focuses on this).

So I think we are on to something really core to what we mean by parallelism.

Hardware view of code: read/compute/write

To make this post manageable, I will explain hardware’s view of software in the most reductionist and simplistic view as possible. A lot will be left out, and other things will be mentioned, but not explored in any detail (I’ll try to find other resources for these things). Unfortunately that means I will be explaining things in a way that is not really completely accurate, but useful for explanation.

Fully imperative programming

In order to help you construct a real assembly language, we need to know what they should generally look like. Now assembly is the medium between the hardware and the programmer (at least it was back when people actually programmed in assembly, not so much any more…). So we need something that can both be implemented reasonably well in hardware, and that the programmer can understand and manipulate easily.

So lets start out with the programmer’s side of things (historically, it was more the hardware side that drove everything, but lets ignore this again).

- Read a small amount of memory from a given address in memory

- Perform some calculation based on that data

- Write back the result to memory

The key insight is that if you consider the program state, such as “the instruction to be executed next”, as data.

Hardware terminology

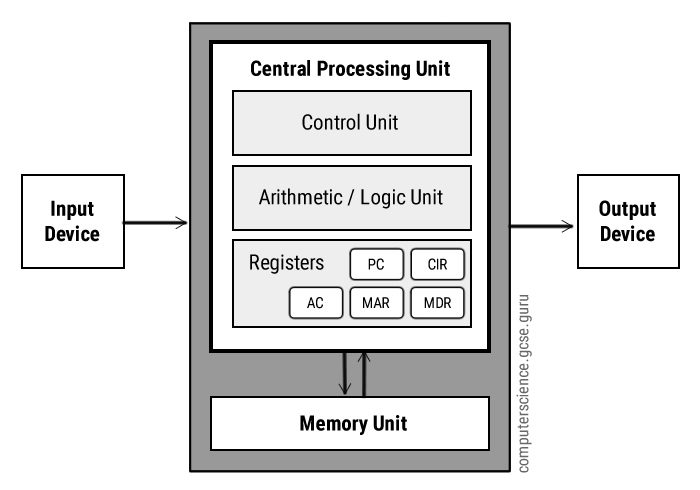

It turns out that the Von Neumann architecture is really not too far from an attempt at implementing an imperative language directly in hardware (this is one of those things that is not historically accurate, but useful for demonstration).

Of course, hardware people came up with all these ideas before programmers did, so the terminology relates to the physical objects, not the ideas.

- Temporary variables are called registers. Of course, there is a fixed number of them, and at least in old computers, they were just fixed memory locations in the CPU to store temporary variables (now, they are not longer fixed hardware locations, and have more symbolic value).

- a

The Von Neumann computer architecture is based on the ideas that programs do 3 things: