Random walks

In terms of fun, well run, accessible and longer competitions, MIT’s battlecode competition is one of the best. I would recommend it if you are ever bored in January.

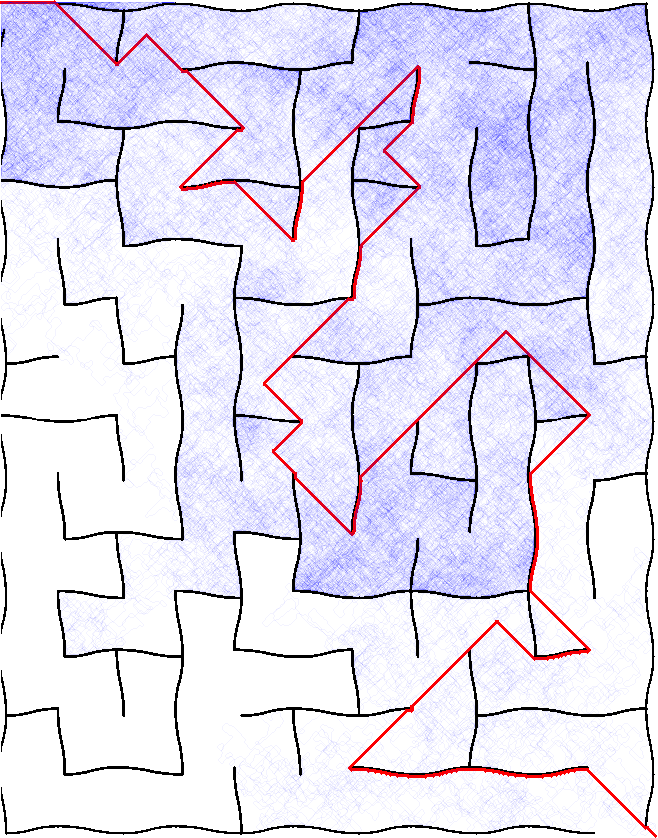

This year, there was a specific feature to the competition I found challenging. The robots operated in a fully continuous space, i.e., there were not a finite number of positions a robot could be in, or move to. Here is a screenshot of what it looked like. Link to view this match (link expires around September 2017).

Now, I have some code which decides on a destination for each robot. My problem is that I don’t know how to get there. After all, how can you make reasonably intelligent decisions about how to get there if there are obstacles in the way? Obstacles which you don’t know about? Especially considering there are a infinite number of possible locations to move each turn? (well, ok, technically not infinite, but very large). I should also mention that there is a very tight computation limit on the decisions (for those who know low level code, it is 10,000 Java bytecodes for all decisions per turn). What this all means practically is that you cannot start building maps of the trees around you and navigate via standard algorithms. Instead, you have to operate with much less information.

Lets try to attack this problem: The code that the competition creators provide has the robots move in a random direction. This is really bad, as the random direction has a small chance of actually being where you want to go. On the other hand, if you move in a single particular direction, you might get stuck (image if the circled robot tries to follow the red arrow). It turns out that this is actually worse than moving randomly!

Ok, so lets abstract away the details and look at the problem closer. I have a robot going from point A to point B. If I just try to go strait to B, then I will probably run into some trees and get stuck.If I move randomly, then I won’t get stuck, but I probably won’t end up where I want to go in any reasonable amount of time. So I want to mix up the to. Lets look closer at random walks in two dimensions to make this somewhat more clear.

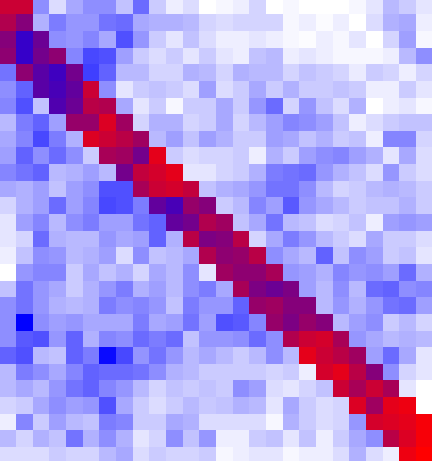

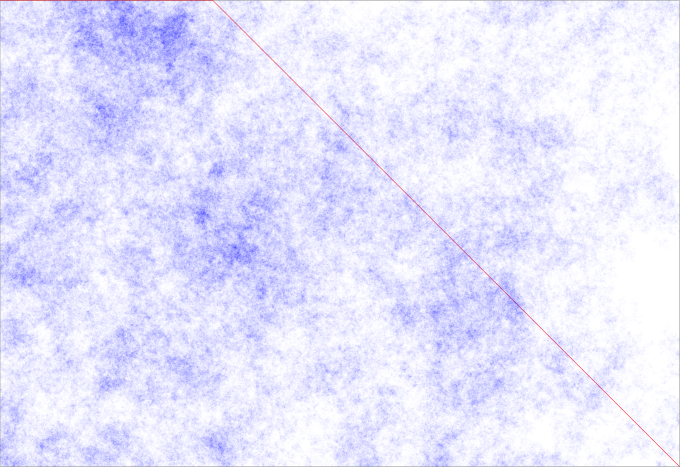

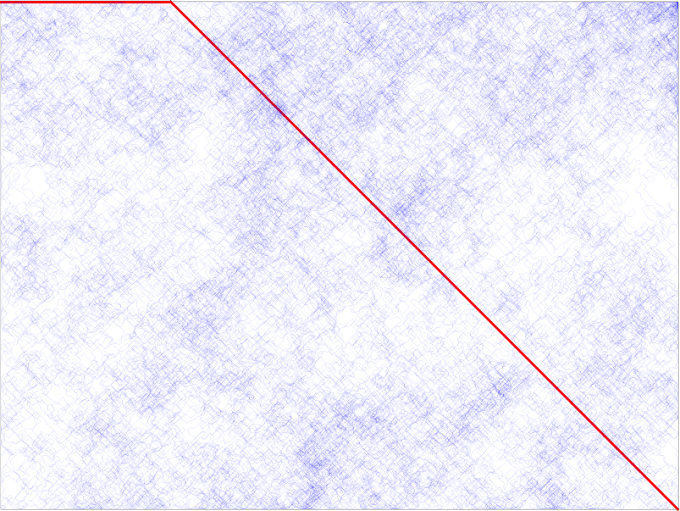

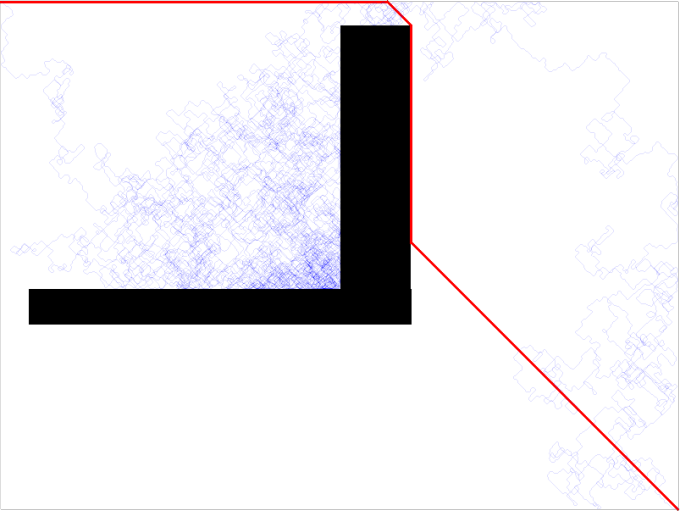

Here is a grid of pixels. I am trying to get from the top left corner to the bottom right corner. The red line goes directly there. The blue stuff is actually a random walk (bounded by the edges of the map) that also goes there. If you are not familiar with random walks, just think that you take steps in random directions until you reach the end. The blueness of the pixel in the output corresponds to the number of times you stepped on that spot.

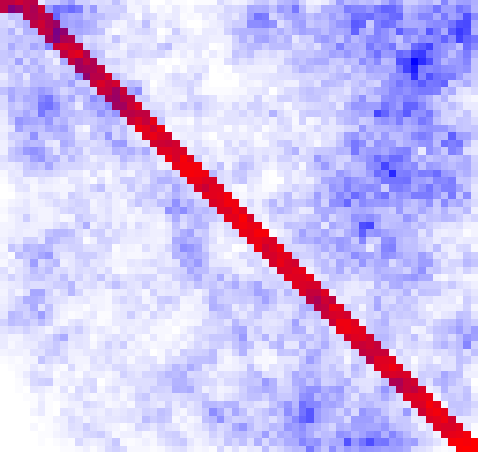

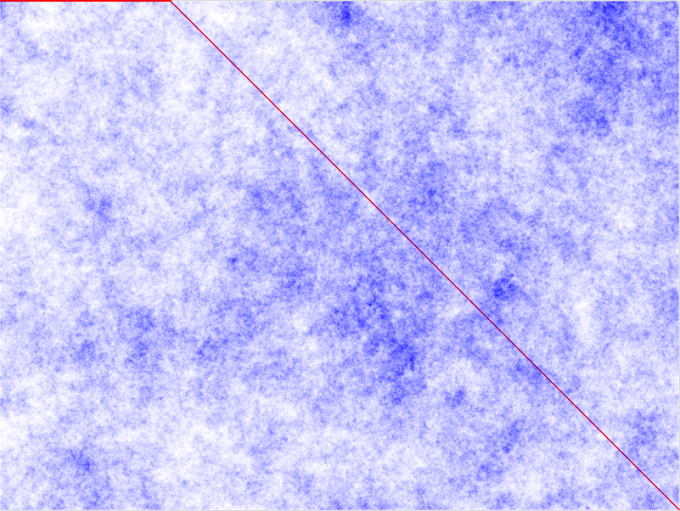

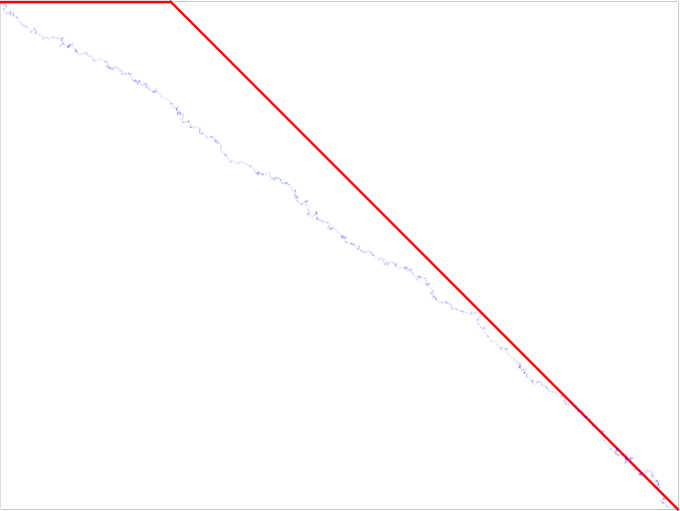

So lets watch the behavior of this line as the space grows:

One thing to note is that this blue path is consistently around 10,000 longer than the red path for the bigger spaces. If you remember our original intentions, it is to move around intelligently in a space we don’t know about. If this takes that much longer than walking strait there, then we might as well not bother. This confirms what I thought originally about the random direction approach being very bad.

However, I have hope that we can find something better, because we already know what the destination is. So perhaps by combining the random walk strategy with the go strait there strategy, we can get a better solution.

How might you go about doing this? If you have a strong math background, then you might have a lot of ideas of how one might do that. I will give a simple way. For problems like this, I really like simple methods. In fact, I think that if your method seems a little complicated to you, there is a lot of value to trying to find a simpler method that works approximately the same. Simple methods are more likely to be correct, make the coding process much faster. And then, you have more time to spend on improving the method. This is most true for approximation algorithms, like the one above.

Back to the problem,

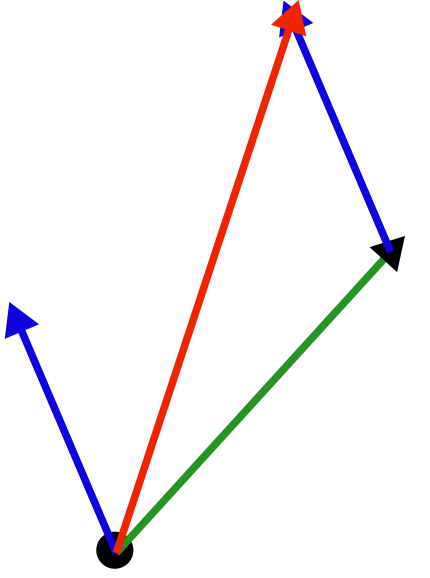

We want to get to the destination. But on the other hand, we still want to have some random element of motion. To me, directions seem like vectors. So what will do is just add a random vector to a vector that points in the direction of the destination.

There are two components here. The blue vector is a vector in a random direction. The green is a vector that points away from where we were last. The resulting direction we want to travel in is the red vector, which is the sum of the random vector and the green vector. This is easy and fast to calculate in code.

def next_dir(curp,destp):

'''

inputs are 2 dimentional vectors

to_xy converts (length, dir) to (x,y), or polar to cartisian coordinates

'''

dest_weight = 0.5

rand_weight = 1.0

dest_vec = normalize(destp-curp) * dest_weight

#to_xy converts (length, dir) to

rand_vec = to_xy(random.random()*2*math.pi,rand_weight)

result_vec = dest_vec + rand_vec

return result_vec.direction()

Working code with details and examples in this github gist. You can run this code easily by copying and pasting the code to this online python interpreter.

There are two additions to the code that I have not yet mentioned. The first are the weights. The weights of 1.0 and 0.5 in the code mean that the vector pushing away from the new point away from the old one will be twice as long as the random vector. The second change is the normalize function. The normalize function makes any vector a length 1 vector. It’s purpose is just to make it easier to think about the weights. It is used so that no matter how far away the previous point is, the force pushing the new one away is the same.

Lets see how well this works!

Wow, that was fast! It got there in 130% of the time of the perfect solution! But remember what our problem was when there was an obstacle in the way.

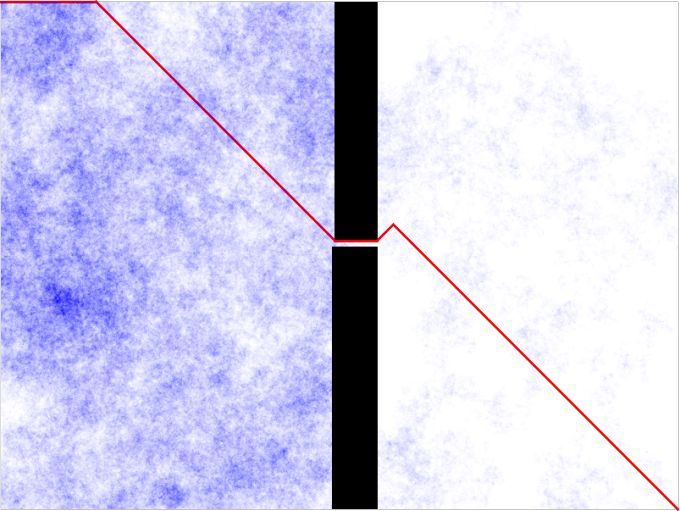

Lets look at this map instead:

With this map, there is a single obstacle in the way, so we can see the random walk’s behavior around it. It turns out that with a dest_weight of 0.5, this will not terminate in my lifetime. I had to lower the dest_weight to 0.015 in order to get this to finish in a few seconds, and it still took over a million steps to get over the barrier.

There is the trace of that walk. As you can see, it is really getting stuck in that corner, and it is getting out by pure chance. Hopefully, you can see that the difficulty it has escaping increases wildly with the size of the area it has to escape. I consider this a failure. If the weight is too low, then there is no significant effect, if it is too high, then it gets stuck. After trying for some time to find an optimal weight, there was still little benefit in this particular case.

But I think we still made significant progress. Why? Because now we have a fairly general method of improving this random walk.

Lets brainstorm another way to improve the walks performance. If you look closer at the cloudy behavior in the random walk, you can maybe see that it is caused by the fact that there is no force pushing it away from where it already is, so it can just move in circles or zigzags, not getting anywhere. I don’t like that. It already knows where the destination is, and I already know where I have been before. I want to be able to incorporate that information in my walk so that it can find the end quicker.

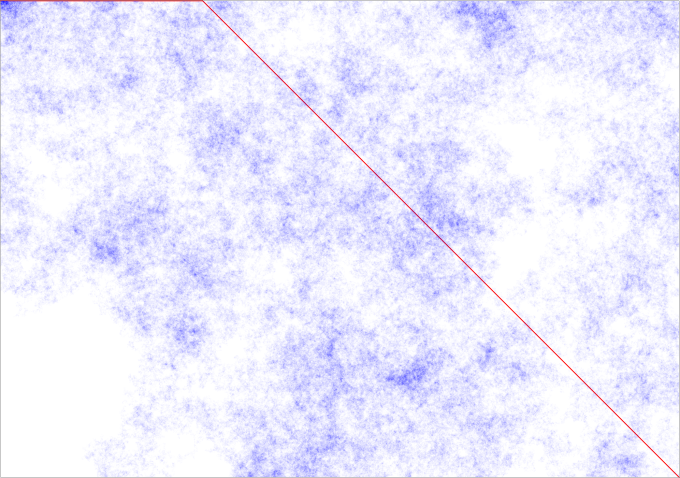

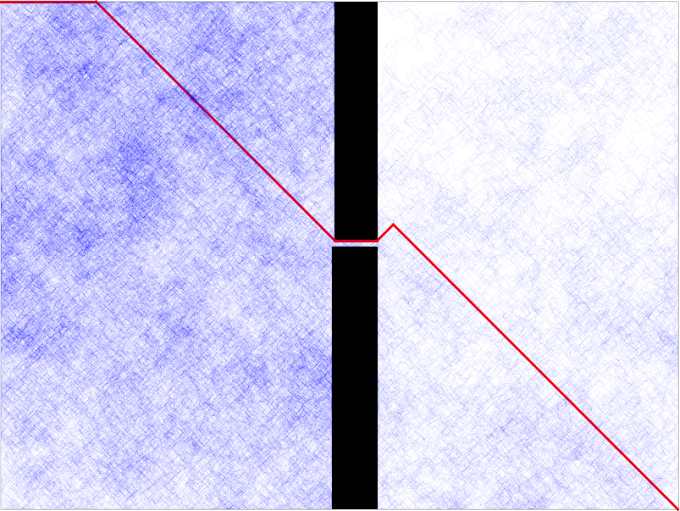

To implement this idea in code we will need to keep track of the place we were last. Then, we can use the same vector technique as last time. The only difference is that in this case, the vector is pointing away from the point we are keeping track of, instead of towards it (which can be accomplished with simple vector negation). Lets see the results:

This looks different! It doesn’t do much better on a blank map, but lets see if it does better on a normal map.

Here is the normal version (9 million steps):

And here is the altered version: (1.5 million steps)

It appears to be doing better, and we can even get a sense of why. The problem where it clusters in a single places does seem to be solved! It really does get to most of the map in the second version.

Lets see how it does on a more complicated maze:

Yup, it still seems to spread itself out pretty well over the map.

At this point of the exploration, I got an idea. If this is spreading over the map, then perhaps it also helps fix the problem that the first idea had, which was that it was sicking in a single point. Lets see how that performs.

Yup, it seemed to work, perhaps even better than without the pull towards the end.

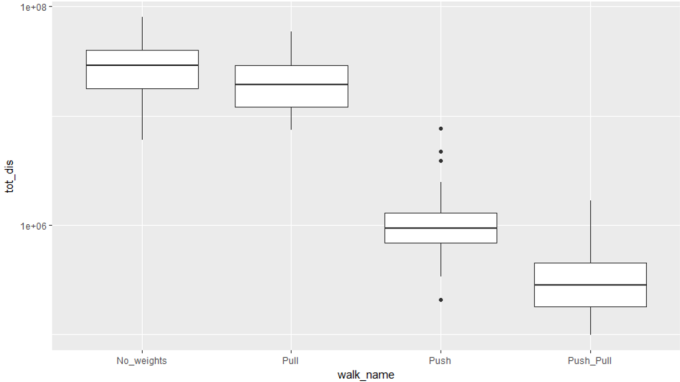

At this point, lets stop to see some more measurable progress. How far have we come? The following measurements are the number of steps it took to go through the more complicated maze given the following techniques. ”Push” is going away from where we started, Pull is being pulled towards the endpoint.

Here we can see that combining push and pull gives a median time of less than 100,000 steps. Considering that the perfect path is 2700, this is still not great, as it is around 35 times longer, but it is now over 100 times better, and usable in certain circumstances. So I will stop trying to improve it, and instead reflect a little.

Potential uses and final inspiration

I will let you in on one of the inspirations for this project. Flies. You have probably seen various flies running into a window, thinking that they are going outside. Now, I have observed houseflies, blue-bottom flies, moths, and even a hummingbird try to get outside through a window that was either closed, or partially open. For them, this situation is similar to our robot walking in the maze, as they don’t know that there is anything blocking them until they run into it.

The animals have different strategies for getting through the window. Some, like the hummingbird and the blue-bottom flies, seem intent on flying strait at the closed window, seemly disregarding its existence, and so they get nowhere. The moths tend to run into the window, crawl around on the window for awhile, and sometimes find their way out. But usually they just hole up in a corner. By far the most successful strategy I have seen is the housefly’s. It runs into the window, goes back in a random direction for some apparently random around of time, and then gets lured back to the brightest light source around. Then it flies at it again. This way, it hits a different spot of the window each time, and so the chance it has of getting out each time is roughly proportional to the area of the window that is open. It can even get away from the window entirely, to a different open window or door, if it is close enough and bright enough. This is how I realized that random, but directed efforts may be the best strategy for navigating in a area where you don’t know where obstacles are.

So if you choose to try to improve this method, you can add new weights, originating from new ideas, or new techniques altogether. But remember the housefly, and try to learn from it.

AI results

In case you were wondering about the AI competition, my long distance movement code was one of the best, at least in my mind. The rest of my code was not so great, so I did poorly in the competition. But I did much better on the type of maps where this long distance movement was needed. So that is some evidence that in this computationally constrained world, this general strategy actually does quite well.

Full code to generate the images is on github. This code is not really meant to be looked at, but you still can if you want.