Introduction to dataset theory

Introduction to Dataset Analysis

Before ~2014, most analysis of machine learning systems focused on modeling decisions, and their resulting problematic underfitting or overfitting behaviors. However, with deep learning the models become so powerful that they can fit to any dataset, and the structure and problems of the dataset starts to matter much more than the structure and problems of the model.

In particular, datasets have little-discussed, but very important corollaries to overfitting and underfitting: overdetermined and underdetermined datasets. I’ll be discussing this mis-behavior, how to identify it in your datasets, and quickly review some techniques to solve this behavior.

Underdetermination

Underdetermination occurs where the input data does not have sufficient information to predict the intended target output labels. This can occur when there isn’t much information to go on, i.e. trying to identify specific faces in a photograph after they have been blurred out. However, underdeterminism can occur even when there is a lot of information to use. A good example in computer vision is trying to predict car velocities from a single photograph frame.

While rough estimates of velocity are possible (basing the guess on other context such as average highway driving speed in that part of the world), it is not generally possible to get precise estimates without at least two photographs at known points in time. For example in the gif below, it is very possible to get accurate estimates of speed, if you know the exact time difference between each frame, and using known reference points such as the length of dotted lines on the highway the cars are driving across.

Bringing this back to the deep learning setting, no matter how high capacity a model you had, no matter how much labeled data you had, if you only have static frames as inputs, you will never expect your model to perform very well in general, because the data is underdetermined. The information you need is simply not present in the image.

Ignore this phenomenon at your own risk. Concrete experimental evidence can lead one to believe that bigger data or better models will fix the problem. This is because the images are so information rich that very complex functions can be learned to make better and better guesses based on population statistics. For example, in the highway example, a model can learn that sports cars are likely to on average have higher speeds than semi-trucks. With bigger data and better models, even more detailed information can be used, including driver age and street position clues that correlate with cars passing each other. This trend of bigger data and models can lead one to believe that the problem can be solved with more data or bigger models. But this assumption will be wrong, and will lead one to wasting time and money collecting the wrong sort of data and training the wrong sort of models.

Human expert estimations of underdeterminism

The good news is that expert human understanding of underdeterminism is usually very good. Very few projects predicated on the opposite assumption of human fallibility succeed. But just to address this more thoroughly, I’ll discuss a few of these rare cases where they do succeed or seem to succeed but in fact don’t and explain the circumstances to look out for.

The main case where human experts fail to recognize solid causal information in source data is when they were never trained on the particular data sources. This could be because

- The expert has simply not been trained on this data source. I.e. the data is coming from a novel detector and the expert does not know what to look for.

- The image data is in a raw format that is not easily readable to a human: i.e. raw ultrasound data (before processing/spatial mapping).

However, more often the expert is right in their assessment of the underdetermination, and the ML algorithm seems to outperform humans on a dataset only by fine-tuned use/abuse of population statistics to overfit to the dataset.

Detecting underdeterminism

Underdeterminism can lead to a variety of model failures, and can be tricky to spot in results. Human expert judgement is the most specific way to identify underdeterminism. However, if this is not available, then some of the other indicators are:

- Train loss does not go to zero, or persistent train-val performance gap remains, even when model capacity is high.

- More data and better labels do not help with training.

Mitigating underdetermined datasets

Underdetermined datasets can be solved by several strategies

- If known context was removed, simply add it back as needed. For example, if scanners give different looking images, instead of training one model that treats the scanners identically, the scanner type can be added as an input to give the model that additional context.

- If guessing is unavoidable and necessary, then try to make sure the model makes the best tradeoffs. Changes to dataset distribution through selective sampling or loss function changes are possible. It is also possible to modify probabilities after training completes to encourage the model to make certain tradeoffs biased towards the more common situation or the safer option.

- If guessing is unavoidable, make sure you are using appropriate regularization and augmentation techniques to avoid problematic overfitting on irrelevant details. Augmentations/regularizations need to be carefully chosen to ensure that the relevant details are preserved, and irrelevant details removed as much as possible. “Light” augmentations such as small color shifts cannot be expected to work well on underdetermined data, as the model will still try to overfit on irrelevant details.

- Label smoothing. Since the label information isn’t fully present in the source data, the predicted label should not attempt to reach high accuracies nor should punish somewhat inaccurate predictions too much.

Underdeterminism is often caused by bad pre-processing or data design choices. For example, when an input video is partitioned down to individual still images prior to labeling or model training, information about relative velocities of objects are simply lost. Or when an image is cropped so that only part of the image is visible, then you can still make a good guess as to high level image information (its taken in a city) but might lose detailed information (which model/make/year of the car is centered in the photo).

Overdetermination

Overdetermination is when there are multiple valid models that fit to the data. I.e. when input data is especially clear or detailed, then many possible features can be used to identify the label.

Why is this a problem? Isn’t it good to be able to pick from a selection of possible well-performing models? The problem is when this occurs concurrently with domain shifts, i.e. when the training data is not representative of the production data. Then

A first example of Overdetermination

Overdetermination is often discussed in the domain of historical analysis. The idea is that when you have some historical trend, there are many possible independent variables, and very few data points. So many possible, reasonable, and well regularized functions fit the same points perfectly. However, most of them do not generalize to the future, and thus do not capture much real information. A good example is predicting the rise of obesity in the United States. There are hundreds of possible indicators, from food sources, mental health shifts, economics, demographic shifts, and very few data points: realistically a single slow moving curve which can be modeled very precisely with just 3 free parameters.

This phenomona is not overfitting because it is not a model design problem, no possible model is capable of reliably fitting the data. Even careful human analysis often fails to fit these sorts of historical trends reliably. Neither can this be solved by collecting more variables to help predict the target data. It can only be solved by finding some way to get more data points.

Overdetermination in vision

Here is a classic example of overdetermination in computer vision: Black bear vs Grizzly bear (plaguing Yellowstone tourists every year).

The problem is that this identification chart tells you many useful features to look for. But if you don’t pay attention to the labels, and only look at the images, you get a bunch of very obvious, but fundamentally unreliable features:

- Fur color

- Fur texture

- Size

None of these obvious features are reliable indicators. Grizzly bears can be small, black, and with smooth fur. Black bears can be fairly large, brown, and with rough fur. This is why this identifier has to tell you to focus on subtle details in body shape instead of these more obvious features. The site where the above identifier was posted immediately shows the following picture of a blonde black bear to prove this point:

And in the wild, things get even more difficult. Its almost impossible to get a picture this clear, so many of these subtle features are occluded or obscured, and so the determination needs to be made on whatever features are clear and available.

This results in a challenging species identification task, where even a single clear identifier should be used in isolation when available. For example, in the following picture, the paws are easily identifiable as a Grizzly bear, but the rest of the bear is in an unusual position and many of the usual indicators are obscured.

To summarize: Overdetermination plus domain shifts can cause models to rely on indicators that will not be available in production.

Overdetermination in computer vision

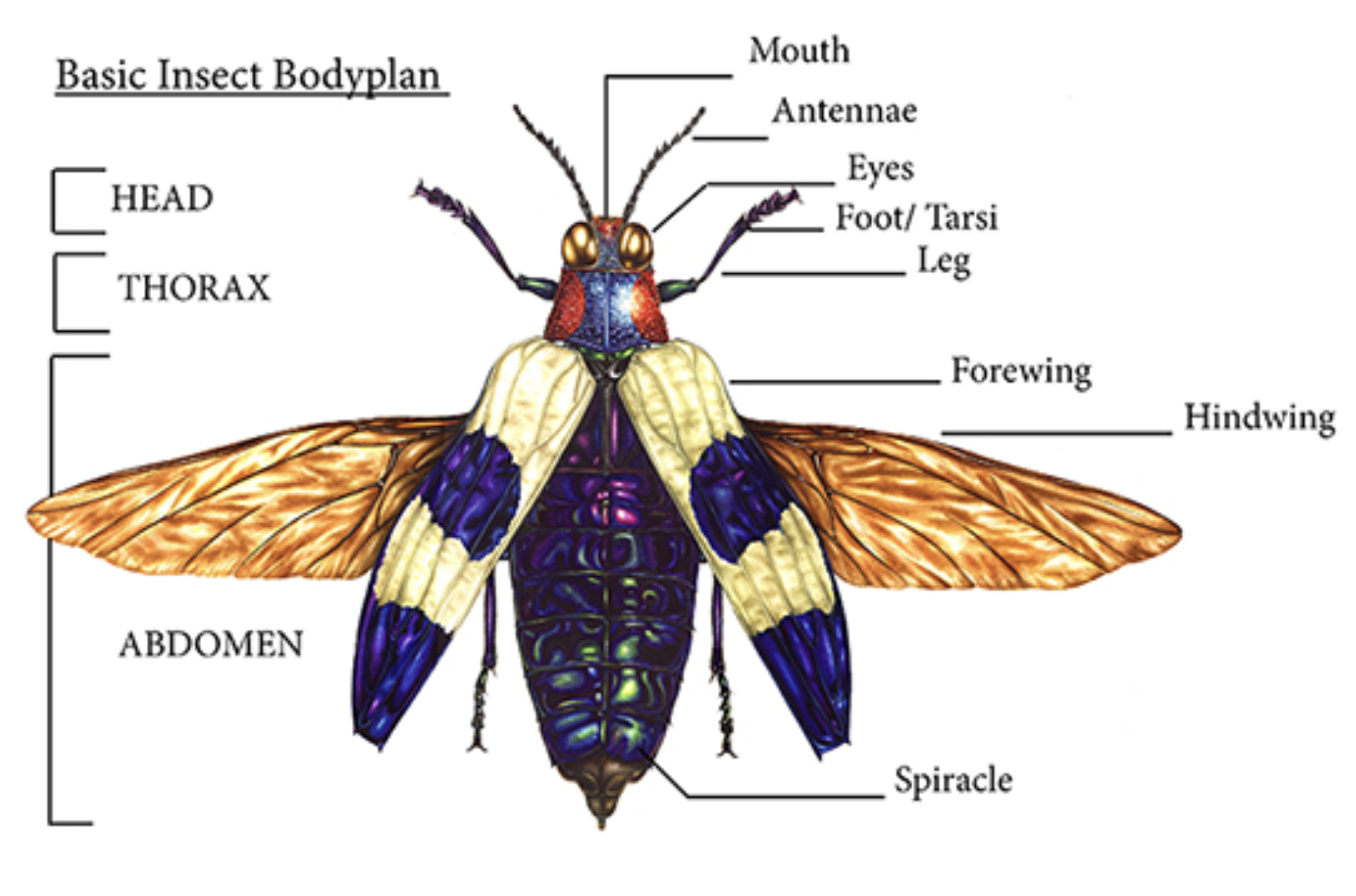

In computer vision, overdeterminism is even more of a problem than when training humans, and even less intuitive. We humans intuitively feel as though many computer vision problems are solvable with very few data points. An entomologist can see a single photograph of a rare species of beetle they have never seen before, and can be expected to do a decent job identifying new photographs of the beetle in the future. And so many people intuit that machine learning systems are able to accomplish a similar feat, learning complex functions from very few data points.

However, this intuition is a false intuition. The reality is that the entomologist was trained on hundreds of thousands of images of beetles, and millions of images of insects. Many of this training data has data known to improve self-supervised learning capabilities, including 3d orientation shifts, time-series frames of live insects, scientific articles about function body parts with detailed annotations, images with clean backgrounds, etc.

This additional context gives powerful ground truth information about the relevant identifying visual information when examining a new type of beetle. Knowledge learned regarding one species generalizes to others, and gets extensively utilized when learning new types of beetles. This prior knowledge is the secret sauce which allows the entomologist to focus in on only a few key identifying criteria, and use these few criteria to reduce the number of independent variables, and transform the beetle identification problem from an overdetermined problem with too many independent variables to a well determined problem with only a few.

Modern deep learning has a variety of techniques to accomplish a similar feat. Models with carefully crafted inductive biases, cross-correlation loss to make a denser loss function (self-supervised learning), fine-tuning regimes to utilize larger related datasets, various augmentation schemes to generate more diverse image-label pairs, and more.

However, no current technique comes very close to matching the data efficiency of human domain experts. And so we do have to treat our datasets with the same care we treat overdetermined datasets in historical analysis, finding ways to make sure the model is learning causal, generalizable information regardless of dataset size or lack of diversity.

Common causes of overdetermination

- Difficulty of Collecting Data: In particular, when objects are very easy to label, i.e. humans can be trained on very few examples, but hard to get examples of, and so insufficiently diverse data is collected.

- Too clean of training data: Can occur when training data is collected specifically for use in some sort of model training, educational, or scientific study (i.e. a medical study) and then the dataset is used for less clean data where fewer features are available.

- Insufficient Preprocessing: Training models end to end on raw data such as pixels, raw audio samples, etc, has been popularized by deep learning, but it does lead to more overdetermined datasets. Effective use of both classical transforms such as FFT analysis, and of deep learning transforms like frozen model features can help a lot

- Too much context: Additional context, especially information about where and when a sample is sourced from, can correlate very strongly with population statistics become more clear indiciators than causual features. Removing context through cropping,

- Insufficient augmentation: Augmentations are human-guided image modeling as to what information in an image is not going to be true causal information.

- Insufficient Modeling: Model design choices can allow some kinds of reduction in image informativeness similar to pre-processing/augmentation.

Identifying Overdetermination

Overdetermination is generally discovered from failures to generalize across datasets/domains, even when performance within a dataset/domain is very good. It can be distinguished from overfitting because well-fitted functions on overdeterminated datasets do not tend to cause train-val splits when these splits are pulled uniformly from the same domain.

Note that unlike underdeterminism, human intuition of overdeterminism is extraordinarily unreliable, with even human experts who are very experienced with machine learning systems having flawed intuitions when the machine learning system changes even slightly. So all investigations into overdeterminism should be backed with numerical results.

This yields the following diagnostic formula:

- Identify domains in my data: collection sites, collection equipment, environmental noise (i.e. time of day/year), etc.

- Split out one data domain for testing, train on all other domains.

- Identify poor generalization on the held-out domain.

- Rule out overfitting by using train-val uniform splits (i.e. in val data pulled from the train domains). Overdetermined datasets with well-fitted functions should not have significant train-val performance gaps, unlike overfitted functions.

Mitigating Overdeterminism

Overdeterminism is fundamentally caused by an imbalance between the amount of unstructured, free parameters in the input set, and the diversity of labels. So one of the best ways to fix overdeterminism is to simply diminish the number of free parameters:

- Heavy Augmentation: I know that this detail isn’t needed, so I’ll destroy the signal with noise: (heavy blurs/large color rotations, large scale changes, etc). This can be extremely effective in many cases, however, if overdone, it will result in an underdetermined dataset, so expert analysis of the augmented images is often beneficial.

- Feature pre-processing: Feature extraction, whether through classical FFT based methods or through processing through a pretrained foundation model, is na extremely effective way of managing overdeterminism by simply rejecting a great number of free parameters. In computer vision, use of foundation models to extract features for later use is becoming a fundamental and foundational technique, reaching state of the art performance in many tasks in data-constrained medical imaginging and data-efficient reinforcement learning. tasks

The other way to fix overdeterminism is to increase the number of informativeness of the labels:

- More data:

- More collection sites

- More distinct samples

- Synthetic data:

- Mixup/mosaic image combinations

- Stable diffusion based image generation

- Simulation image captures

- Out of domain data/Transfer learning:

- Standard pretraining sets (i.e. imagenet)

- Domain-specific training sets (i.e. medsam)

- Additional loss functions:

- to get it to learn specific informative features of the data and bring them out. I.e. self-supervised cross-correlation losses.