Building High Performance Pipeline Processing Tooling in Python

“Don’t reinvent the wheel”: often great advice, but programming is a big world, and sometimes you are looking around, and there seems to be a gap in the tooling: you want a wheel, but there only seem to be logs or Conestoga wagons available. I.e. the appropriate high level tooling just doesn’t exist (everyone custom-builds their own solutions), or is simply overly complex (existing tooling requires complex configuration with many sharp edges and potential bugs).

Once the challenge is confronted, the general lack of tooling identified, and the call to build something something completely new is rising in your heart, then we get to face the great challenge of bringing the new tooling to the world of highly constrained real world software. This great challenge ended up being less like a classroom assignment, and more like a dungeon boss raid in a D&D style game.

I was quite pleased with how this pipeline processing project turned out, with a satisfying design and low-level implementation merging with an impactful real-world engineering project, and I’m share this experience in incremental tooling development out of the hope that others can envision paths to fruition on their projects.

The Call to Adventure: Encountering costly but rewarding problems

Every new idea starts with a challenge, an uncomfortable situation, where there is uncertainty, risk, and potential rewards. A call to adventure.

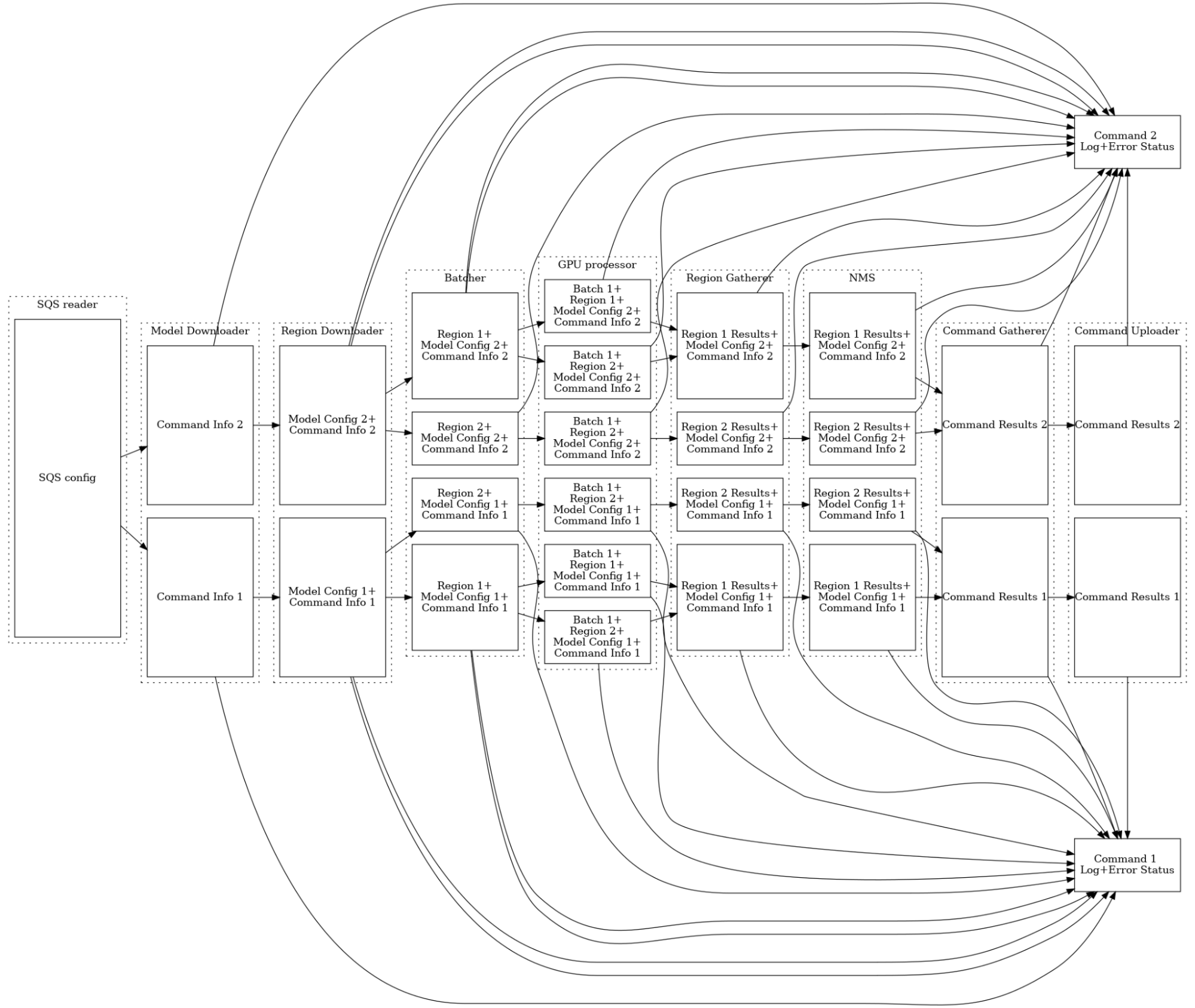

In this case, there was this dungeon of complexity around this ML inference pipeline that I worked on in 2021. This inference system was a distributed queue-worker based system. Each GPU worker was also optimized to maximize efficiency and reduce costs. However, the worker was optimized in an quick-iteration, make it work at all costs manner, using knots of deeply nested and overlapping mess of multi-processing, multi-threading, pipes, queues, events, error handling, etc. After the original developer was promoted out of the team, the code was broadly viewed as incomprehensible and unmaintainable, and every one of us warrior coders gave up on solving the existing race conditions, unintuitive dependencies, infinite loops, deadlocks, etc, and instead hacked on an increasingly deep nest of timeouts, retries, and other failsafes to whack the sputtering engine into chugging along as best as possible.

But at the end of this cavern was treasure:

- The ability to actually change the code to be more general and more future-proof without fearing the goblins overwhelming us during the process

- The hope of a more robust system with fewer intermitted stalls and crashes.

- Clear, measurable inefficiencies in GPU utilization, with immediate AWS cost savings on the order of tens of thousands of dollars a month.

This treasure was clearly visible across the engineering group, and somewhat valuable to leadership, shining on efforts to success from on high.

Despite this potential treasure, and its visibility, simply formulating a plan to solve the problem perfectly was beyond any of us working there, as there were regulatory commitments to never change any results of any existing models, and a codebase that couldn’t be iterated on without breaking something, and a lack of a clear mission, leadership, or resources stymied any serious planning.

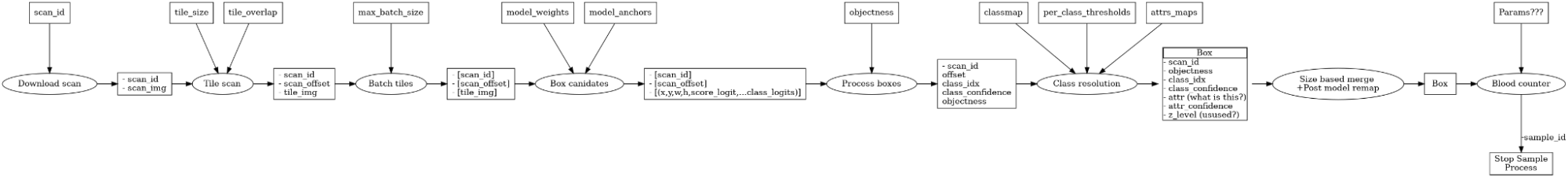

However, the warrior coder must remain vigilant and prepared against all threats, both those highly visible and those that are obscured. So I traced every logical codepath, and diagrammed out into what seemed like the best logical abstraction: a data processing pipeline (original janky diagram of the actual pipeline sketched out below). It wasn’t pretty, but it made me understand the inherent simplicity to the logic. The cave was dark, and packed with monsters, but not too big or deep.

At this point, without a clear path to success, and with other tasks pulling at my mind, this effort stalled for about 6 weeks, pondering it occasionally, and slowly gaining confidence for a deeper dive into technical solutions to the principles of pipeline processing in ML inference, and the unavoidable problems implied by python multiprocessing.

Gearing for the Last Boss: Prioritizing the hardest problem

“Python multiprocessing bug”. This phrase tends to strike anxiety into the hearts of even those software developers experienced with multithreading in other computer languages or systems. It certainly struck some anxiety to all of us working on this system.

And it isn’t just that our codebase was particularly messy, as it is a dreaded problem across the entire python data processing ecosystem. Most python-based high performance data processing frameworks includes “multiprocessing support” as a cool add-on feature to improve performance (i.e. pandas, scikit-learn, dagster, ray, etc). Unfortunately, in seemingly every single one of those systems, this feature has an long trail of bug reports, performance concerns, and other usage difficulties. These difficulties often add up to hundreds of hours of wasted effort from downstream developers, and stress that could have been avoided simply by using another language with better parallelism support. And so python multiprocessing is often the most prominent issue that pushes developers to look for an alternative to python, even at great expense and losing the great advantages of python’s incredible computational ecosystem.

But what if we started from scratch, and built a micro-framework architected specifically around python multiprocessing difficulties, rather than trying to add in support later? What if we geared up to face the last boss, from the very beginning?

Luckily, I had a great deal of prior experience with python multiprocessing, from my prior experience building PettingZoo multiprocessing wrappers. I also had solid academic knowledge of low-level OS provided primitives to share data and synchronize processes, from TAing a course on the subject during grad school. Also some basic knowledge of the underlying guarantees the hardware provides for cross-thread memory consistency.

The experience led me to know some of the core issues that cause most of the pain, bugs, and poor performance that other libraries encounter. I.e. I had scouted the last Boss’s special attacks:

- Unhandled Segfault: Many computational tools in the python ecosystem are built on top of C/C++ extensions prone to segfaults. These segfaults completely bypass all normal python exception handling, and ruin most multiprocessing error handling schemes, leading to indefinite hanging, most often mitigated by expensive busy-polling.

- Mismatched error propagation: Even normal python exceptions, which are handled by all libraries, can have minor but annoying semantic programming issues. In particular, the propagated errors when multiprocessing is enabled can look different than errors when multiprocessing is disabled, often leading to discrepancies in test and production environments.

- Excessive memory cloning: When a new process forks, it takes a copy of the entire process image, even the stuff it will never access and doesn’t need. This often leads to programmers limiting the amount of parallelism far below the capacity of the CPU, just because memory is constrained instead. (and for OS nerds out there, no, in python, the OS support for copy-on-write memory process clones does not fix this very well, perhaps due to writes caused by python’s cyclic garbage collector passes or some other memory sweeper.)

- Spawn multiprocessing overlooked: Spawn multiprocessing is the only officially supported method on MacOS, and the only method period on Windows. However, spawn multiprocessing re-constructs the entire python runtime environment, resolving imports which requires running the script section of the python code, meaning that stateful behaviors in the script section of the python environment are vulnerable to bugs and problems. Combined with linux-heavy dev teams, this overlooked technical challenge can lead to lots of Mac/Windows specific bugs occurring.

- Excessive usage of unix pipes for bulk data transfer: Unix pipes are a powerful abstraction for inter-process communication. However, they are built on-top of a 65kb buffer, which creates a lot of unnecessary back-and-forth process chatter which slows down the data transfer significantly. Their implementation also includes a large set of locks, kernel context switches, and other sources of overhead that reduces their performance even for smaller data transfers.

Sketching out key design principles

With a commitment to focus on these concrete system/runtime problems, rather than abstract software design principles, the design fell into place quickly.

- This would be a microframework that fully controls how and when processes are spawned, errors are handled, and messages are passed. Users will only have access to a fixed set of configuration to change semantic behavior. This decision goes against many of my closely held software design principles, but it seemed like the only way to make sure every one of those failure cases were handled.

- The core microframework would only support a single very simple concept: linear async message passing between workers. All other features and functionality would be built on top, either in the form of coding patterns, or in the form of wrappers with a higher level interface with more features. This decision to only support linear message passing rather than general directed graphs like some competitor systems (i.e. dagster) was mostly to make backpressure—the killer feature of any low-latency pipeline processing system—easier to implement and analyze.

- Default parameters would be set to maximize stability and accuracy over performance, allowing users to opt-into performance gains only when necessary.

Sketching out the API:

When designing the high level API, I thought of the familiar, beautiful way of achieving pipelining in unix: the shell command pipe.

$ cat sample.a | grep -v dog | sort -r

While this cannot be elegantly translated one to one to python, I remembered this idea from my previous employer that python generators are the most pythonic equivalent of unix pipes. Each “command” is turned into a generator which accepts an iterator, and returns an iterator:

"""

Awfully similar semantics to unix pipe

load_images | run_model | remap_results | aggregate_results

"""

img_iter = load_images(imgs)

model_results = run_model(img_iter, model_name="yolov5s", model_source="ultralytics/yolov5")

post_processed_results = remap_results(model_results, classmap= {0: "cat", 1: "dog"})

final_result = aggregate_results(post_processed_results)

print(final_result)

Refining the gear: Low-level tips and tricks

With this basic design in place, the basic implementation of the core functionality was fairly simple. Simple enough that a bunch of optimizations and tricky components could be added while keeping the whole implementation under 1000 lines of code, making it relatively easy to code-review. These tricks included the following optimizations:

- A custom pipe-based asynchronous communication system for unbounded, foolproof communication.

- Configuration to enable the use of a custom-built, fixed size, preallocated process-shared memory buffer with the

multiprocessing.RawArraypython interface for fast, high bandwidth communication - Pickle v5 out-of-band-buffer protocol to maximize read/write efficiency to the shared memory buffer. Only supported in python 3.8 and above. Gets 3-4x performance improvement for large buffers vs ordinary pickling.

- Support for multiple workers in each pipeline step to allow data parallelism to occur efficiently in the same framework.

- Custom ring buffer protocol to match up many producers to many consumers via a fixed number of buffers (of either type). This custom protocol enables the critical parallelism suppression feature of the system using clever semaphore usage allowing for infinite multi-step backpressure.

Even more importantly, this simplicity allowed for fairly exhaustive testing of configuration options and many exceptional cases of segfaults, spawn multiprocessing, and error catching.

Performance turned out pretty good as well: when fixed-size buffers are enabled, tens of thousands of short messages can be passed per second, and multiple gigabytes of single-connection total message bandwidth for larger messages. Process spawn time is typically well under a second, and shutdown triggered by either exceptions or segfault typically also well under a second. There are no busy loops enabled by default, so CPU overhead is very low. All powered by a pure-python implementation with only pure-python dependencies.

With a customized build and gear designed specifically to tackle the last boss, it should be a breeze. Now it is time to turn our attention to the rest of the dungeon.

Awaiting the Arrival of the Hero: Leadership Comes from Above

While individual bosses might be soloed by the well prepared, whole dungeons cannot be so easily soloed, as a wide variety of skills, knowledge, relationships, and centers of focus are needed to win every battle and evade every trap (the real world does not have save points or respawns). So Dungeon clearing parties need leaders to establish common objectives and bring people together, and sometimes, we are not the right person to do that. Sometimes, we have to just wait to be hired into a party.

In my case, I was lucky, as a leader arrived only a few weeks after I had done the above preparation. He came quietly, but quickly: secretly building out a prototype ML model for our most successful product in a couple of weeks, revealing the prototype to select influential executives to buy support for his project, quietly inviting a hand-picked team of engineers to work on the plan, all while continuing his prior role as a backend team lead and evading the inevitable pushback from the normal engineering management hierarchy until momentum had developed.

As you might expect from this description, he is the main hero in the greater story surrounding this one, and I am merely a well-prepared mercenary-type side character. He later revealed his immense frustration with the status quo of stale leadership, high operating costs, and bad code, that caused him to reach across the company wanted to help save the company from its reliance this legacy ML codebase and its poor outcomes. We ultimately found a lot of common ground in this frustration and quickly built a trusting relationship.

In this greater picture, the last boss I had been preparing for was revealed to simply be a stage boss, and not the most ugent to defeat nor the scariest. In this greenfield project proposal where everything was a rewrite, order and priorities had to be completely rethought. So to start, I volunteered to work on dataset pre-processing and configuration, putting aside the classifier/inference project as a lower ambiguity, lower risk boss that I was better prepared for.

But sure enough, a couple of months later, the team members’ focus had shifted, the classifier was still unfinished, and after getting dataset construction and training sorted out, the classifier was still more or less unchanged from the initial kick-off prototype. So I was ready to take on this stage boss, once and for all. But before that, I had to navigate a few traps.

- Team lead: Why is your pipeline design better than my design in the prototype?

- CTO: Did you do a literature review of the alternative technologies? Can you submit a short writeup of these alternatives and why they aren’t adequate?

My solution to the first one trap was pretty standard: a slew of design diagrams, bottleneck analysis, tradeoff documents, etc. But all of these arguments were ultimately unconvincing. Later, he revealed that was was unconvinced by my arguments or by the pipeline lib design until several months later when it was deployed into our fully scaled production system with no problems. So instead, the primary outcome of this whole slew of documents ended up being a simple demonstration of my commitment to the design and the heart to see it through to a successful completion.

The second issue I ignored. While the CTO was a phenomenal engineer with great practical sense, he was too far away from the project to control its course, and he had already signed off on the basic principle. All he was doing with this suggestion was trying save the company time and sorrow by making sure we weren’t reinventing the wheel. But I was already convinced that there was no such wheel, only the aforementioned logs and Conestoga wagons so I just ignored it, and the issue was dropped because implementation progress was steady.

After everything was said and done, several months later, the actual production classifier on most of our products ended up adopting the pipeline inference framework, and the CEO was pretty pleased about all the AWS cost savings, and the engineering management was pretty pleased about the additional flexibility, and everyone was happy. Except for me, because I was made a team-lead to make sure all this new infrastructure had the necessary support to make it to production successfully. And I was the one with the most technical expertise and knowledge of the systems. But after the business hurdles to getting the code to production were crossed, and operational difficulties settled down a bit, I managed to wiggle myself out of the leadership role, and started to have the space to think about where this core pipeline processing framework needs to go.

The Dungeon Needs a Walkthrough: Implicit feature support in microframeworks via examples and tutorials

Software development is much like game development: there are a few hardcore devs out there who want to solve every problem themselves, but most people just want to complete the challenge, regardless of what help they receive. So if you want to make a micro-framework like this successful, it needs to have easy, established ways to solve most common problems brought to it. This does not always require code: typically documentation, examples, and tutorials provide the necessary solutions just as effectively as coded features. This understanding that documentation can replace code is the key difference in philosophy between a microframework and a macroframework.

The best way to consistently improve this documentation is to just write guides for the rooms and minibosses in rooms that you and your collaborators have already explored, encourage others to do the same, and hope that they are useful to others.

So after some dungeon crawling through the exiting production codebase that inspired the project, trying to smash my head against every single feature of the existing code, even if minor, or a convenience feature, or a significant performance optimization that could be added, and translated it to this pipeline concept, I ended up with a less detailed, but more functional diagram of everything that easily fit into the pipeline concept, and the few things that didn’t:

This diagram tries to communicate two important features I encountered that do not fit easily into the pipeline processing concept effectively because they require tracking state across pipeline steps:

- Chunking bigger parts of work into smaller ones for consistent pipelining performance across a wide range of input sizes.

- Short-circuiting on errors

- Job-specific log-capture/occasional log uploading.

All three are great examples of real-world complexities that come up all the time and cause consternation and concern when trying to adopt this sort of framework in a team environment in the real world.

Problem 1: Chunking/Gathering work across pipelines

Chunking is easy in the framework

def split_jobs(task_generator: Iterable[Job])->Iterable[JobPart]:

for new_job in task_generator:

for job_part in chunk_job(new_job):

yield job_part

Merging back the results in a future pipeline step after processing is complete is relatively strait-forward if all of the jobs have only a single worker, as we can assume that the job parts are processed in-order:

@dataclass

class JobPart:

parent_job_id: str

part_result: PartResult

previous_job = None

job_part_results = []

for job_part in task_generator:

if job_part.parent_job_id != previous_job:

if previous_job is not None:

yield combine_results(job_part_results)

job_part_results = []

previous_job = job_part.parent_job_id

job_part_results.append(job_part.part_result)

if job_part_results:

yield combine_results(job_part_results)

It becomes somewhat more complicated if there are multiple workers per task in any of the processing steps, but the idea is the same, except it has to handle out of order sub-tasks, especially who’s parents occur out of order. So one has to track how many sub-tasks each job was split into so we know when it is fully finished.

Problem 2: Short-circuiting on errors

If we don’t want to kill the whole pipeline on an error, but also can’t continue processing because the data is simply missing, or we want to save CPU time, we can skip downstream processing tasks very simply like this:

for new_job in task_generator:

try:

# do some process that can error

...

yield job_result

except Exception as err:

handle_error(err)

# simply don't yield the result and it won't be passed on to the next task

Or, if we really want to count errors in the downstream handler, or something along those lines, we can pass the error forward in intermediate tasks like this:

for new_job in task_generator:

if isinstance(new_job, Err):

# if it is just an error, then pass it along to

# the next step so it can be handled without

# interrupting parallel work in the pipeline

yield new_job

else:

#

....

Problem 3: Job-level log upload

If we want to have some state mutated constantly throughout the pipeline, like an error log, we can just pass around a file pointer, and have a coding convention to append to a file like this:

for new_job in task_generator:

# open up a job-specific logfile for writing, redirect logger/stdout to it

with new_job.job_guard():

# actually do the computations/network requests/etc

....

# when the context guard closes, upload the log file

# if it hasn't been uploaded in awhile

This context guard can redirect the global logger or stdout to a file just for this process, just for this particular code chunk, allowing different jobs in different parallel workers to append to fully separate log files. A different file for keeping track of the last uploaded time was also maintained so that the log could be updated if the context guard exits, and if there has been a 30s gap since the last timeout, whichever one comes first, implementing the occasional log upload efficiently but synchronously.

Current status

This project is currently awaiting final approval for an open-source release. Code link and full-code examples/documentation are awaiting this release.